Do You Live in DC? Have You Been Getting a lot of Political Ads on YouTube? Here’s Why.

Kennedy Ruml used to not mind YouTube ads.

An ad popping up was like looking down while out with friends and seeing her shoelace had come untied. Annoying? Yes. But not annoying enough to ruin the moment.

Over the past year, Ruml has lost her desire to watch YouTube videos after an increase in right-wing advertisements in favor of President Donald J. Trump. She usually laughs them off or ignores them completely. However, Ruml is put off by the tone of the ads. “They ruin the mood a little. They almost jumpscare me.” She commented.

Ruml doesn’t normally watch political content, instead opting for reaction videos or gameshow-style videos from channels like Cut. Despite her viewing habits, Ruml describes being flooded with ads. “The frequency has increased a lot over the past year. It doesn’t seem to have slowed down since the election; it seems to have picked up.” Ruml said, noting that since November of 2024, she has seen more and more of these ads.

Ruml isn’t imagining it. Between November 5th of 2024 and 2025, political advertisers on YouTube spent significantly more per capita in Washington, DC, than anywhere else in the nation. Washington, DC has only one non-voting delegate in the House of Representatives and no senators. It isn’t a swing state, and there were no major elections in 2025. Yet, advertisers spent nearly $3.23 per resident, which was a little more than eight times the national average of 40 cents.

Tensions between DC residents and the president are nothing new, with over 92.5% of residents voting for Democrat Kamala Harris over Trump. Yet dozens of political groups, funded by undisclosed donors, have poured nearly 2 million dollars into ads that support Trump. Matthew Hindman, a Professor of Media and Public Affairs at the George Washington University, says that the target of these ads is likely not voters, but policymakers.

NBC4 Washington investigated a similar pattern earlier this year, but on broadcast TV rather than YouTube. In April, several viewers wrote to the station complaining that “campaign-style” ads were still airing months after the election. NBC4 responded by airing a segment attempting to identify the groups behind the ads; reporters found little beyond the organizations’ names and mailing addresses.

Although no comparable reporting exists for YouTube ads, researchers have long raised concerns about the platform’s content algorithm pushing viewers toward right-wing material. A 2023 study published in PNAS by UC Davis researchers found that as users engage with right-wing political content, they are increasingly recommended more extreme and conspiratorial videos.

However, YouTube’s ad algorithm operates differently from its content algorithm — and its political ad system is even more restricted. Political advertisers can target users only by age, gender, and location. They may also use contextual targeting, which places ads alongside videos with relevant titles or themes.

These limits on political ad targeting, combined with parallels between TV and YouTube advertising, raise a key question: How does Washington, D.C. compare to the rest of the country in political ad spending per capita — and is this oversaturation a national trend, or a uniquely local one?

The Google Ad Transparency Center (GATC) is the entity that publishes Google’s ad data, such as advertisers, ads, and ad spend. The GATC is more transparent with political ads than non-political ads; it’s relatively easy to find data on total ad spend across the country and the world.

Using the GATC and its available parameters, I gathered the total ad spend from each individual state and DC between November 5, 2024, to November 5, 2025. In terms of total ad spend, California, Virginia, and New Jersey lead, while DC ranks at 15th.

However, total ad spend doesn’t tell the full story. Per the 2024 US Census Population Estimates, 702,000 people live in DC, which is less than in most states and even many global metropolitan areas. Because of this, 2 million dollars has more of an impact in DC than 2 million dollars in a state with more people, like a majority of states.

To calculate the true impact of DC’s total ad spend, and the rest of the countries, I divided the total ad spend by the total population estimate based on the 2024 US Census Population Estimates. With this, I had calculated how much advertisers had spent per capita, rather than the entire state.

At $3.23, advertisers spend significantly more per capita than in any other state. There are still a few outliers, but each can be easily explained. Virginia and New Jersey are still outliers, but this is explained by the highly competitive gubernatorial elections held on Election Day this year.

Maine and Alaska are also outliers, but a glance at each state’s top spenders gave two swift explanations. In Maine, the top spender, the Majority Forward Fund, had bought ad space for an $838,000 campaign against Senator Susan Collins (ME-R). Coincidentally, the Majority Forward Fund was also the top spender in Alaska and had bought ad space for a $378,000 campaign against Senator Dan Sullivan (AK-R).

The Majority Forward Fund was also a top spender in DC. Instead of focusing on local politicians, their DC campaign highlighted Senators Collins and Sullivan, alongside other senators from other states. Furthermore, when I tried to find more information on the Majority Forward Fund, I couldn’t find an organization by that name.

This group is likely a SuperPAC or an issue advocacy group, like the clandestine groups NBC4 Washington was unable to interview. According to OpenSecrets, a SuperPAC is a political group that can raise unlimited amounts of money in support or against a candidate.

In some spheres, people also refer to them as issue advocacy groups, although this term has also been used to refer to “dark money” organizations. For this article, however, these groups will be referred to as issue advocacy groups, as most of them focused on specific issues like healthcare costs, immigration, or the government shutdown in their ads. SuperPACs typically refer to groups that either support or rally against candidates.

Even though these organizations are supposed to disclose their donors, many obfuscate this information by passing their donations through “dark money” channels such as 501(c)(4)s nonprofit organizations or shell companies.

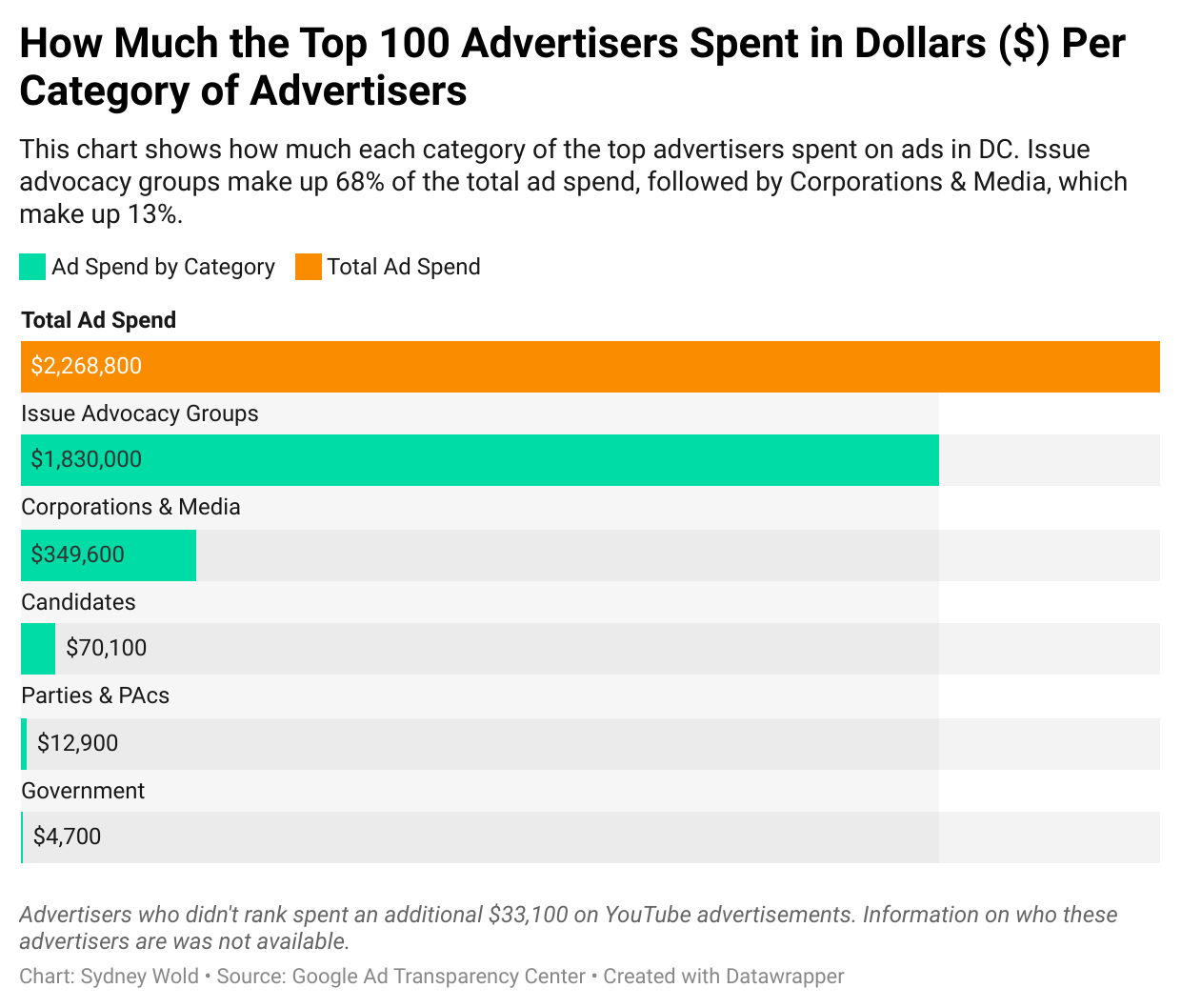

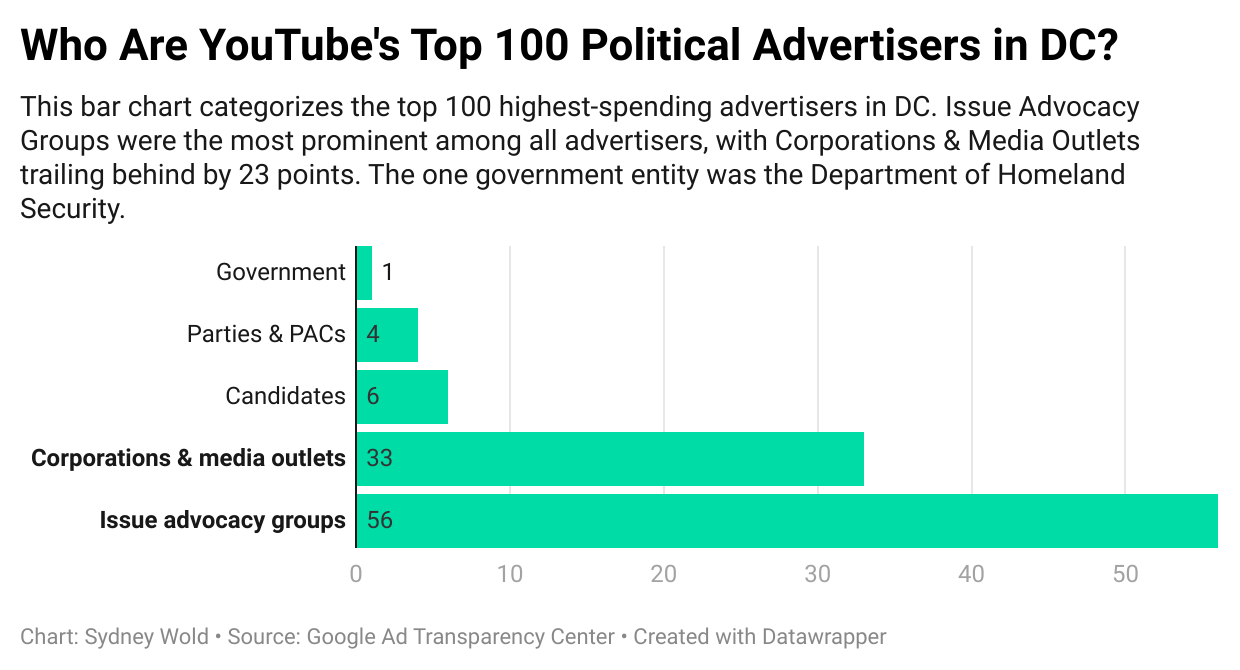

The Majority Forward Fund, based on their campaigns against multiple Republican senators, appears to be Democratic. In DC, however, most of these SuperPACs/issue advocacy groups are more decisively Republican. These issue advocacy groups also made up 68% of DC’s total ad spend, with over $1.8 million.

Out of political candidates, PACs, corporations, and the government, issue advocacy groups were represented the most across the biggest spenders in DC, accounting for 55 out of the top 100 spenders.

The presence of these issue advocacy groups is an alarming one, due to their secretive nature. As seen on NBC4, there’s no way to figure out what their goals are or why they are publishing these ads beyond speculation.

Although the true intentions of these organizations can’t be determined, some experts have an idea of who they are trying to reach. Matt Hindman, a professor of Media and Public Affairs at the George Washington University, posits that advertisers are releasing these ads in the hopes they will end up on the screens of policymakers.

“There is clearly a desire to target policymakers. These agencies are likely buying lots of YouTube ads because targeting isn’t precise.” Hindman commented.

It’s important to note that Google prohibits political advertisers from using geographic radius targeting, or targeting audiences based on whether they're in the radius of a specific building, landmark, business, etc. For instance, a pizza place may use geographic radius targeting to show advertisements within five miles of their establishment.

In practice, that means political groups can’t laser-target the White House or Capitol Hill. Instead, they have to buy ads across wider swaths of the D.C. area, which can be as small as a zip code or as large as the whole United States.

Most D.C. viewers, like Kennedy Ruml, are simply caught in the spillover. They aren’t the ones these groups are actually trying to persuade, yet they see the brunt of the messaging, with little transparency about who is paying for it or why. Issue advocacy groups dominate the city’s ad spending and often operate through channels that obscure their donors, leaving both journalists and viewers guessing about their motives.